215 lines

32 KiB

Markdown

215 lines

32 KiB

Markdown

### Casper The Friendly Finality Gadget

|

|

|

|

This document describes a candidate design for the first implementation of Casper proof of stake on Ethereum. The proposal aims to achieve the key goals of deposit-based proof of stake including highly secure finality and low-cost consensus, but do so in a way that can be applied with minimal disruption to existing chains, including the current Ethereum proof of work chain. We describe the workings of the algorithm, show safety and liveness in a partially-synchronous fault-tolerance-theoretic model, and then proceed to describe the various considerations involving game-theoretic incentives, as well as how the system can automatically recover from >1/3 of nodes dropping offline, and with the use of lightweight out-of-band coordination assumptions, recover from various forms of 51% attacks. We will describe the algorithm in stages with increasing complexity, in order to show the core ideas first, and then bring in features such as validator set rotation and economic incentivization.

|

|

|

|

### Background

|

|

|

|

Proof of stake has for a long time been viewed as a highly promising, but controversial, alternative to proof of work as a way of securing cryptoeconomic public blockchain consensus. Whereas proof of work measures economic consensus by measuring the quantity of computational resources that have been expended to "back" a particular state and history, proof of stake in simplest form seeks to replace physical mining with CPUs, GPUs and ASICs with "virtual mining" [cite], where economic consensus is measured by the economic resources inside the system that are committing to a given state and history.

|

|

|

|

However, early versions of proof of stake suffer from a flaw that is often called "nothing at stake" [cite], which states that if one naively builds a proof of stake algorithm by simply copying the intuitions and algorithms from proof of work, then the result is an algorithm where, in the event of a disagreement between whether to choose chain A or chain B, it is in every rational participant's interest to choose both. Unlike proof of work, where resources _on the outside_ can be applied to either chain A or chain B but not both, in naive proof of stake the very fact of a chain split means that there is also a temporary split of the ledger of on-chain economic resources, and so a validator can use their copy of the resources on chain A to back chain A and a copy of their resources on chain B to back chain B.

|

|

|

|

PoW

|

|

<img src="https://raw.githubusercontent.com/vbuterin/diagrams/master/powsec.png" width="400px"></img>

|

|

PoS

|

|

<img src="https://raw.githubusercontent.com/vbuterin/diagrams/master/possec.png" width="400px"></img>

|

|

|

|

Casper builds on a tradition that was started with the description of [Slasher](#) in early 2014, which attempts to explicitly detect such "equivocation" (a common Byzantine-fault-tolerance-theoretic term for the act of sending two messages that contradict each other, in this case by simultaneously supporting two conflicting forks), and economically penalize validators that are caught engaging in such behavior in order to discourage it.

|

|

|

|

<img src="https://raw.githubusercontent.com/vbuterin/diagrams/master/slasher1sec.png" width="400px"></img>

|

|

|

|

This solves nothing at stake (at the cost of an extremely weak synchrony assumption ("weak subjectivity") that will be discussed later), and ensures that such proof of stake algorithms can be at least as secure as proof of work. However, we can go further. It was soon discovered by Vlad Zamfir that consensus algorithms based on penalties could be made vastly more secure than consensus algorithms that are purely based on rewards, because there is an inherent asymmetry between the two. Whereas rewards are inherently limited in the size of the incentive that they offer, as every reward paid out must be paid out by the protocol, penalties can theoretically go much higher, potentially even all the way up to the entire pool of capital that the participant is participating in the proof of stake mechanism with.

|

|

|

|

This allows for the introduction of a notion of _economic finality_:

|

|

|

|

> A block, state or any constraint on the set of admissible histories can be considered _finalized_ if it can be shown that if any incompatible block, state or constraint is also finalized (eg. two different blocks at the same height) then there exists evidence that can be used to penalize the parties at fault by some amount $X. This value X is called the _cryptoeconomic security margin_ of the finality mechanism.

|

|

|

|

However, such strict forms of penalty-based proof of stake run into another risk: the possibility of "getting stuck":

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A poorly designed algorithm could lead to a situation where it is not possible for any new block to be finalized, without at least some participants taking some action that would lead them to incur the penalty. Making an algorithm that can provide genuine finality, and that also avoids the possibility of getting stuck under all but the most exceptional circumstances, is a difficult challenge - but one that maps very well to problems that have already been studied for a long time under the aegis of Byzantine fault tolerance theory.

|

|

|

|

Algorithms such as PBFT, Paxos and HoneyBadger BFT [cite * 3] all try to achieve a similar goal, of achieving "consensus" between some group of nodes (sometimes called "processes"). An early attempt at defining the problem was through the Byzantine general's problem, where a group of generals are trying to coordinate on a specific plan for how to attack a city, but some of the generals may be traitors. The two goals are:

|

|

|

|

A. All loyal generals decide upon the same plan of action.

|

|

B. A small number of traitors cannot cause the loyal generals to adopt a bad plan. [cite Lamport 1982]

|

|

|

|

In a consensus algorithm implemented in real life, the "plan of action" to be decided on is that of which operations are to be processed in what order.

|

|

|

|

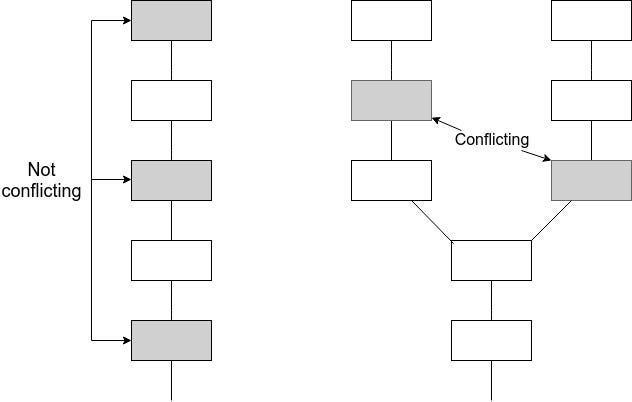

In our case, the goal is not just to have one round of consensus to agree on a single value, but rather have ongoing rounds of consensus on an ever-growing chain. In a blockchain, every block contains the hash of the previous block, and so it is inherently linked to a history containing ancestor blocks going all the way back to some "genesis block" that was agreed to as one of the parameters of the protocol. Coming to consensus on a block inherently involves coming to consensus on all of its ancestors. Hence, the consensus algorithm must avoid not just coming to consensus on two conflicting blocks during one period, but rather it must also avoid coming to consensus on a block when it has already come to consensus on a block that conflicts with one of the block's ancestors.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

We will start off by presenting "Minimal Slashing Conditions", a mechanism that has this property, and that can also arguably be used in other contexts as a simpler alternative to PBFT.

|

|

|

|

### Minimal Slashing Conditions

|

|

|

|

This algorithm assumes the existence of an underlying **proposal mechanism**, which creates a chain of blocks which is constantly growing, and where given a set of blocks there is a way to deterministically calculate what is the "tip" of the chain. The chain may grow in a perfectly orderly fashion, with one block being added to the tip every few seconds, or it may sometimes have "forks" where a given parent block has two children and one of the two children is eventually abandoned, or in the worst case the chain may grow highly chaotically, with multiple long-running branches with the identity of the tip constantly switching from one chain to another.

|

|

|

|

The proposal mechanism working with a relatively high level of quality is not necessary for safety; provided more than 2/3 of nodes correctly follow the protocol conflicting checkpoints will not be finalized no matter how poorly the proposal mechanism behaves. However, if the proposal mechanism behaves very poorly, this may prevent liveness.

|

|

|

|

The proposal mechanism is deliberately kept abstract; this can be a dictator, it can be a round-robin scheme between the participants in the consensus, or, as in our case with hybrid Casper, it will be the original proof of work chain.

|

|

|

|

Every hundredth block in the chain is called a **checkpoint**, and the period between two checkpoints is called an **epoch**. We assume the existence of a set of **validators** V<sub>1</sub> ... V<sub>n</sub>, with sizes S(V<sub>1</sub>) ... S(V<sub>n</sub>); in hybrid proof of stake each of these validators must have put down a deposit, and the amount of ETH in that deposit becomes their size.

|

|

|

|

Validators have the ability to send two classes of messages:

|

|

|

|

[PREPARE, epoch, hash, epoch_source, hash_source]

|

|

[COMMIT, epoch, hash]

|

|

|

|

The intention is that during epoch `n`, validators wait for the proposal mechanism to create a checkpoint during epoch `n` (say, with hash `H`), and then create a PREPARE message for epoch `n` and hash `H`. The `epoch_souce` and `hash_source` values should refer to the most recent (in terms of epoch number) checkpoint that they know about that has received prepares from a set of validators PREPSET where `sum_{v in PREPSET} S(V) >= sum_{v in ALL_VALIDATORS} S(V) * 2/3` (hereinafter, we will refer to a set which has this property as "at least two thirds of validators"; any reference to a fraction of the validator set should be read as being weighted by size). If/when at least two thirds of validators create a PREPARE for `n` and `H` with the same `epoch_source` and `hash_source`, validators should then send a message to COMMIT `n` and `H`. If two thirds of validators do this, the checkpoint is considered finalized.

|

|

|

|

Although we say that validators "should" follow the above set of rules, in many circumstances there is no way to enforce that they are in fact doing so. For example, consider a case where the proposal mechanism forks and creates two competing checkpoints at epoch `n`, C1 and C2. Suppose that a validator sees C1 five seconds before C2. According to the above rules, the validator _should_ prepare on C1. However, if the validator prepares on C2, this cannot be detected, because for all we know the message containing C1 _could_ have been delayed by six seconds en route to that validator's computer and so the validator could have seen C2 first.

|

|

|

|

However, what we _can_ do is identify a few specific cases where there is clear evidence that a validator acted incorrectly, and in these cases penalize the validator heavily - in fact, we can even go so far as to take away their entire deposit.

|

|

|

|

We can do this by defining a set of "slashing conditions", where if any validator triggers one of the four conditions they will lose their entire deposit. The conditions are as follows:

|

|

|

|

[copy from medium post https://medium.com/@VitalikButerin/minimal-slashing-conditions-20f0b500fc6c, "The slashing conditions are:" up to but not including "With these four slashing conditions, it turns out that both accountable safety and plausible liveness hold."]

|

|

|

|

We would like to prove two properties about this mechanism:

|

|

|

|

1. **Accountable safety** : if two conflicting hashes get finalized, then it must be provably true that at least 1/3 of validators violated some slashing condition.

|

|

2. **Plausible liveness**: unless at least 1/3 of validators violated some slashing condition, there must exist a set of messages that 2/3 of validators can send which finalize some new hash without violating some slashing condition.

|

|

|

|

Details of a machine-verifiable proof in Isabelle can be [found here](https://medium.com/@pirapira/formal-methods-on-some-pos-stuff-e309775c2ab8). A proof sketch is as follows:

|

|

|

|

Suppose that two conflicting hashes C1 and C2 get finalized. This means that in some epoch e1, C1 has 2/3 prepares and 2/3 commits, and in some epoch e2, C2 has 2/3 prepares and 2/3 commits (if either of those sets of 2/3 prepares were missing, 2/3 of validators would have violated `PREPARE_REQ`).. First, consider the easy case where e1 = e2. Then, 2/3 prepares on C1 and 2/3 prepares on C2 require 1/3 of validators to have violated `NO_DBL_PREPARE`.

|

|

|

|

Now, without loss of generality, consider the case where e2 > e1. By `PREPARE_REQ` the 2/3 prepares on C2 imply 2/3 prepares during some previous epoch e2' < e2. This in turn implies 2/3 prepares during some epoch e2'', and so forth until one of two terminating cases:

|

|

|

|

(i) e2\* = e1. Here, we have 2/3 prepares on C1, and 2/3 prepares on some ancestor of C2 which is not C1, and so 1/3 get slashed by `NO_DBL_PREPARE`

|

|

(ii) e2\* < e1. Here, we have 2/3 prepares with `epoch > e1` and `epoch_source < e1`, as well as 2/3 commits with `epoch = e1`. Hence, at least 1/3 of the preparers must have violated `PREPARE_COMMIT_CONSISTENCY`

|

|

|

|

Plausible liveness can be proven even more easily. Suppose that (i) P is the highest epoch where there are 2/3 prepares, and (ii) M is the highest epoch when any message has been sent. By (i) there were no honest commits with epoch above P, and so 2/3 of validators can safely prepare any value with epoch M+1, and epoch source P. They can then safely commit that value.

|

|

|

|

### Hybrid fork choice rule

|

|

|

|

The mechanism described above ensures _plausible liveness_; however, it does not ensure _actual liveness_ - that is, while the mechanism cannot get stuck in the strict sense, it could still enter a scenario where the proposal mechanism gets into a state where it never ends up creating a checkpoint that could get finalized.

|

|

|

|

Here is one possible example:

|

|

|

|

<img src="https://cdn-images-1.medium.com/max/800/1*IhXmzZG9toAs3oedZX0spg.jpeg" width="400px"></img>

|

|

|

|

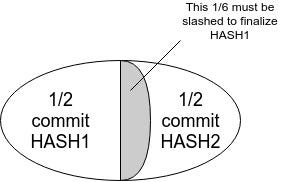

In this case, HASH1 or any descendant thereof cannot be finalized without slashing 1/6 of validators. However, miners on a proof of work chain would interpret HASH1 as the head and start mining descendants of it. In fact, when *any* checkpoint gets k > 1/3 commits, no conflicting checkpoint can get finalized without `k - 1/3` of validators getting slashed.

|

|

|

|

This necessitates modifying the fork choice rule used by participants in the underlying proposal mechanism (as well as users and validators): instead of blindly following a longest-chain rule, there needs to be an overriding rule that (i) finalized checkpoints are favored, and (ii) when there are no further finalized checkpoints, checkpoints with more (justified) commits are favored.

|

|

|

|

One complete description of such a rule would be:

|

|

|

|

1. Start with HEAD equal to the genesis of the chain.

|

|

2. Select the descendant checkpoint of HEAD with the most commits (only checkpoints with 2/3 prepares are admissible)

|

|

3. Repeat (2) until no descendant with commits exists.

|

|

4. Choose the longest proof of work chain from there.

|

|

|

|

The commit-following part of this rule can be viewed in some ways as mirroring the "greegy heaviest observed subtree" (GHOST) rule that has been proposed for proof of work chains. The symmetry is this: in GHOST, a node starts with the head at the genesis, then begins to move forward down the chain, and if it encounters a block with multiple children then it chooses the child that has the larger quantity of work built on top of it (including the child block itself and its descendants). Here, we follow a similar approach, except we repeatedly seek the child that comes the closest to achieving finality. A checkpoint is implicitly finalized if any of its descendants are finalized, and so we need to look at descendants and not just direct children. Finalizing a checkpoint requires 2/3 commits within a single epoch, and so we do not try to sum up commits across epochs and instead simply take the maximum.

|

|

|

|

### Adding Dynamic Validator Sets

|

|

|

|

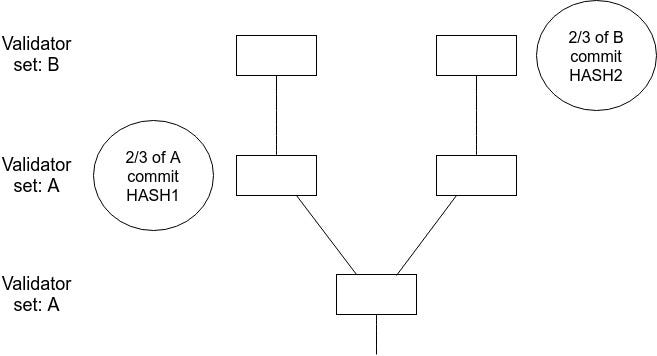

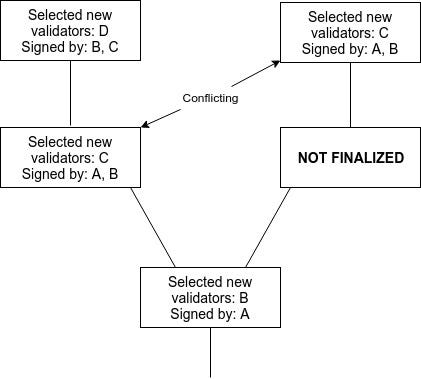

The above assumes that there is a single set of validators that never changes. In reality, however, we want validators to be able to join and leave. This introduces two classes of considerations. First, all of the above math assumes that the validator set that prepares and commits any two given checkpoints is identical. If this is not the case, then there may be situations where two conflicting checkpoints get finalized, but no one can be slashed because they were finalized by two completely different validator sets.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hence, we need to think carefully about how validator set transitions happen and how one validator set "passes the baton" to the next. One nautral possibility is to only change the validator set if an epoch was finalized. This resolves the problem in its simplest form, as it means that there is no way to skip to the next validator set without finalizing a block with the previous validator set first.

|

|

|

|

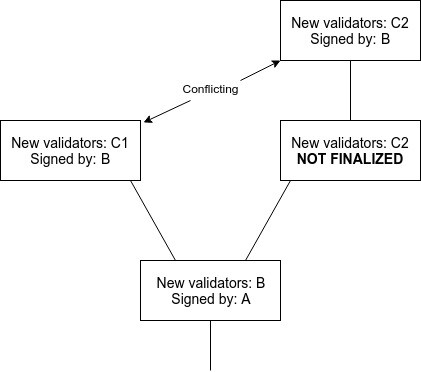

However, this is still not a complete solution because it fails to take into account that the fact of whether or not an epoch was finalized _is itself something we do not yet have consensus on_. Hence, there exists a possible failure mode where two children get made on top of the same parent, where from one child's view the parent was finalized and from the other child's view the parent was not finalized:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

There are three ways out. One is for nodes to wait for two rounds of "finality" before considering a block finalized; one cannot achieve finality for both children without the signatures of the second round on one side and the first round of the other side intersecting. A second is to limit the rate at which validators can be swapped in and out, ensuring fault tolerance still stays close to 1/3. A third is to require signatures from both 2/3 of the current validator set and 2/3 of the previous validator set in order to consider a set of prepares or commits sufficient.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

We make one modification to the fork choice rule: instead of taking the descendant with the highest percentage of commits from "the" validator set, we take the descendant checkpoint where the _minimum_ of (i) the percentage of that checkpoint's _current_ validator set that committed, and (ii) the percentage of that checkpoint's _previous_ validator set that committed, is maximized.

|

|

|

|

### Joining and Leaving

|

|

|

|

Now, we need to establish what is the specific mechanism by which validators can join and leave. We start off with a simple one:

|

|

|

|

* Validators apply to join the validator set by sending a transaction containing (i) the ETH they want to deposit, (ii) the "validation code" (a kind of generalized public key), and (iii) the return address that their deposit will be sent to when they withdraw.

|

|

* If this transaction gets included during dynasty N, then they become part of dynasty N + 2, as well as all future dynasties until they decide to log off.

|

|

* Validators can "log off" by sending a transaction to do so. If it is included during dynasty N, then they will be logged off starting from dynasty N + 2.

|

|

* If a validator has been logged off for the past consecutive four months, then the validator can send another transaction to withdraw their deposit to their return address.

|

|

|

|

The two-dynasty delay ensures that the joining transaction will be confirmed by the time dynasty N + 1 begins, and so any candidate blocks that initiates dynasty N + 2 is guaranteed to have the same validator set for dynasty N + 2.

|

|

|

|

Note that the possibility of validator sets changing, and validators withdrawing their deposits, opens up another risk: **long-range attacks**. If a client has been logged off for more than four months, then there is a risk that a malicious majority of former validators, who were active at the time the client was now online but are now no longer active, can finalize a chain conflicting with the main chain, send this chain to the client, and the client will accept it. This necessarily means that at least half of this malicious majority violated a slashing condition, and under normal circumstances it would mean that their deposits are fully lost. In this case, however, _the offending validators have already taken their money out_; hence, they cannot be penalized.

|

|

|

|

This problem is not fully resolvable, unless we are willing to adopt a system where validators can never recover their deposits. What we _can_ do, however, is better understand the precise requirements that we are imposing on clients and the network. A message should be considered "cryptoeconomically meaningful" only if the message is signed by a validator whose deposit is still certainly in the main chain. The way we can test this is that the client can keep track of the time that they most recently received a each finalized checkpoint, and only accept a child checkpoint if this checkpoint is received less than four months after the predecessor. This implies that in order to remain synchronized with the chain, clients need to be logged on every four months, and assuming clients are online constantly it implies a network synchrony assumption: any message signed can reach any node within two months (half of four months, as if a client detects a validator violating a slashing condition, the message needs to be included into a block before that validator can withdraw in order to destroy theire deposit).

|

|

|

|

### Economic Fundamentals

|

|

|

|

The fault-tolerance-theoretic assumptions made so far simply assume that more than two thirds of every validator set is not willing to lose theire entire deposits, and given this assumption we can show safety. However, we must also show how the algorithm incentivizes liveness, and so so under several different sets of assumptions. We analyze the proof of stake component under both an uncoordinated choice model and a coordinated choice model. For now we assume that the underlying proof of work blockchain simply works, and ask our readers to accept this in light of uncoordinated choice modeling [cite http://nakamotoinstitute.org/static/docs/anonymous-byzantine-consensus.pdf] and empirical observations that coordinated attacks on proof of work have been rare so far, though in a later section we will discuss how validators can cooperate to overcome 51% attacks against the underlying proof of work layer.

|

|

|

|

### Protocol utility function

|

|

|

|

We will start off by specifying a "protocol utility function", a function which can be computed on any chain and which outputs a value that represents the "quality" of the chain. A unit decrease in protocol utility should be understood to represent a unit decrease in user satisfaction; our main objective when designing the incentive mechanism is to align incentives to maximize expected protocol utility. The utility function has no role in the actual protocol; it is simply a philosophical tool that we can use to evaluate how "good" a particular protocol execution is.

|

|

|

|

We define protocol utility as follows:

|

|

|

|

sum_{epoch i = 1 ... n} -ln(i - LFE(i)) + c[i] - M * SF[i]

|

|

|

|

Where:

|

|

|

|

* LFE(i) refers to the last epoch in the chain before block i that was finalized (in an optimally running chain, this is always i-1)

|

|

* SF[i] = 1 if a safety failure was detected in epoch i, as defined by 1/3 of validators getting slashed, otherwise 0

|

|

* c[i] is the portion of commits in epoch i

|

|

* M is a (very large) constant

|

|

|

|

Note that there is no single principled way to say what the protocol utility is; this is a question that ultimately rests on the values of the users of the system. However, we can defend the reasoning behind each component in the above formula.

|

|

|

|

The -M * SF term is self-explanatory; safety failures are very bad, as it means that events that appear to have been finalized, and that users may be relying on being finalized, suddenly become unfinalized. The -ln(i - LFE(i)) term is more complicated. What is it saying is that the amount of pain that users feel from having to wait `k` epochs for their transaction to be finalized is logarithmic in `k`. This can be justified inuitively: the difference between finality in 1 minute and 2 minutes feels similar in size to the difference between 1 hour and 2 hours. The separate `c` term is there to show that even if a given epoch does not finalize, commits can still provide value, as a smaller number of commits on a given block can still make it harder to finalize competing blocks.

|

|

|

|

### Recovering from Coalition Attacks

|

|

|

|

Suppose that there exists a coalition of size >= 1/3 (possibly even size >= 2/3) that engages in attacks of type (5), (6) or (7) above. This type of attack can be resolved in honest nodes' favor, but in many cases (especially those where the dishonest coalition is of size >= 1/2) this requires some out-of-band coordination between users, which can only partially be automated. This does require a synchrony assumption between validators and users, but one on the order of weeks (more precisely, the synchrony assumption must be on the same order as the amount of time that a >33% attack will take to resolve; resolution taking weeks is arguably acceptable because the prepetrators will lose a large portion of their deposits in this kind of attack).

|

|

|

|

Such an attack and resolution would proceed as follows. First, suppose that a validator with >= 1/3 of nodes simply stops committing, or logs out outright and stops committing and preparing. The two cases are alike so we can consider just the first.

|

|

|

|

The offline validator loses `(NCP + NCCP * 1/3 + NFP) * PENALTY_FACTOR` times their balance. Online validators lose `(NCCP * 1/3 + NFP) * PENALTY_FACTOR` times their balance. With the "griefing factor bound 2" settings of (1, 1, 1, 1, 0), this gives a loss (expressed as percentage of total deposit) of 1 + 1/3 for the offline validator and a loss of 1/3 for online validators, so the offline validator's balance drains four times as quickly. If the online validator's share is 40% (ie. offline validator has 0.4x, online validators have 0.6x), for example, then the blockchain will once again commit when the balances decrease to (offline 0.272, online 0.545), at which point online validators once again have more than two thirds.

|

|

|

|

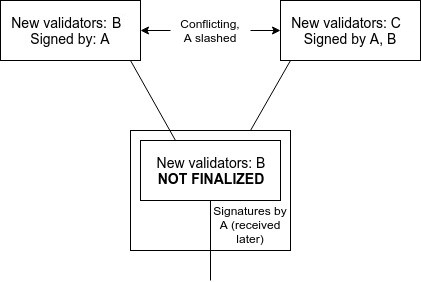

Note that this real-time reduction of deposits does introduce a new consideration: if there are two conflicting checkpoints that finalize, the validator sets between the two checkpoints can now differ. In the most extreme case, this implies the possibility of two conflicting finalizing checkpoints where on one of the two checkpoints no deposits are lost. For example, consider the case of two finalized checkpoints C1 and C2, where C1 comes one epoch after the previous finalized checkpoint, but C2 comes long in the future. Suppose that the validator set is split into groups A and B, where A finalizes C1 and B finalizes C2. At the time of C1, the size of A is 0.667x, and the size of B is 0.333x. At the time of C2, the size of A is reduced to 0.111x, and the size of B is reduced to 0.222x. Hence, A can finalize C1 and B can finalize C2 with no slashing conditions violated.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The purpose of this attack would be to convince a node that has been offline between C1 and C2 that C2 is the correct chain, when in reality it is C1 that is the correct chain. B would lose a large portion of their deposits on the C2 chain, but the C2 chain has little economic value as it is only used for this one particular attempt to defraud a set of clients, and so the attacker would emerge unscathed on the C1 chain.

|

|

|

|

This can be resolved by strengthening the synchrony assumption. If the node is constantly online, then it should refuse to accept C2 until three weeks have actually passed, and so as long as C1 can reach the node within three weeks there is no security risk (more precisely, latencies that are significant but below three weeks can reduce the amount of equivocation needed for double finalization, perhaps from 1/3 to 32.5% if latency is a day or 25% if latency is a week, though the exact figures depend on the exact formula used).

|

|

|

|

Here are the results for the formulas above; note that the delay until finality can easily be scaled proportionately by any value.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

### Recovering from Majority Censorship Attacks

|

|

|

|

Now, let us consider the attacks where the censoring coalition is >= 1/2. Then, minority validators will refuse to build on chains that are censoring them, and so they will coordinate on their own chain. The result will be exactly the same as the result above: a majority chain and a minority chain, where under the rules of the protocol the majority chain will be able to finalize first, and where on the majority chain the victims will lose money faster than the attackers and so the attackers will be even stronger.

|

|

|

|

The asymmetry can be broken because users can manually implement a "user activated soft fork" where they refuse to accept the majority (attacking) chain, and so they can simply wait until the minority chain sheds deposits to the point where a checkpoint can be finalized by the non-colluding nodes. This coordination can be partially automated, as online nodes will be able to detect censorship, but it's impossible to make the automation perfect (as a perfect solution would violate impossibility results in distributed consensus); hence, a preferred solution is for nodes to give an alert if they believe the majority chain is attacking, and give the user an option of whether to continue with the majority chain or fork to the minority chain.

|

|

|

|

### Dealing with Failures in Proof of Work

|

|

|

|

In this kind of design, the underlying chain is still generated by proof of work. However, there is much less need to worry about 51% attacks on the proof of work for several reasons.

|

|

|

|

There are three kinds of 51% attacks in proof of work:

|

|

|

|

* **After the fact finality reversion** - make a chain longer than the existing main chain, reverting a large number of blocks at the end of the existing main chain that were thought to be finalized.

|

|

* **Equivocation** - create two "main chains" A and B that both appear long enough to be the main chain; convince one actor that A is finalized and another actor that B is finalized.

|

|

* **Censorship** - refuse to include blocks and transactions from other miners.

|

|

|

|

Finality reversion is impossible outright for miners to carry out, as finality is defined by the finality gadget and not proof of work; this immediately eliminates the worst kind of 51% attack. Equivocation can be used to prevent finality by repeatedly creating multiple chains with different checkpoints for each epoch, so that validators never manage to put two thirds of their prepares behind a single one. Censorship can be used to prevent validators from being rewarded, along with the first-order consenquences of making the chain unusable.

|

|

|

|

If worse comes to worst, equivocation can be dealt with manually by having validators come together over an out-of-band communication channel to coordinate on finalizing checkpoints until a hard fork to replace the proof of work can be conducted. However, there is also another more automatable approach: validators can start ignoring checkpoints unless their proof of work meets a higher difficulty threshold. Suppose that malicious miners have an n:1 advantage against honest miners, and malicious miners need to create c competing checkpoints to reliably prevent convergence (say, c = 3, as if c = 2 then one of the two may easily get two thirds prepares by random chance). This will eventually lead to the situation where the malicious miners will attempt to create c admissible checkpoints and publish them simultaneously, and ~1 - c/n of the time they will succeed, but the other c/n of the time an honest miner will create a single checkpoint first, and the consensus will move forward.

|

|

|

|

### Selective Censorship Attacks

|

|

|

|

Another kind of attack is that where either (i) >=1/3 of validators or (ii) >=1/2 of miners _selectively censor_; for example, they might fully cooperate within the consensus protocol but refuse to include transactions that match some blacklist. This can be dealt with by giving validators and users a _subjective fork choice rule_: they assign lower scores to blocks that appear to be not including transactions that should be included, and if censorship looks unambiguous they simply reject such blocks entirely.

|

|

|

|

This then degrades into a few cases:

|

|

|

|

1. >=1/2 of miners selectively censor; >=2/3 of validators do not participate. Then, the validators will simply coordinate on finalizing the longest non-censoring chain.

|

|

2. >=1/3 of validators only sign chains that are selectively censoring. Then, from the point of view of non-participating validators, those validators are offline, and so this situation collapses into the liveness attack described in a previous section.

|

|

3. Validators wrongly believe that censorship is taking place, because a network synchrony assumption is violated. In this case, some validators end up refusing to prepare or commit checkpoints that they would otherwise be preparing or committing, and so fewer or no blocks finalize until the network synchrony assumption once again takes hold.

|